This piece appeared in PRN Magazine in July 2015

Nursing in crisis: The disappearing numbers

A pay-freeze, a row over safe staffing and new rules to kick thousands of nurses out of the country: it’s been a stormy summer in medical politics. Benedict Cooper reports.

And, finally, to round off a torrid month, in his budget the Chancellor delivers the news that the pay freeze on all public sector workers is to continue – for four more years.

“Getting tough on migrants might play out well with the public, but anyone who has worked in an NHS hospital knows how crucial these workers are for the service.”

Take any one of these decisions in isolation, and you will find nurses reeling as a result. Take them all together, and it begins to feel like a concerted effort.

Getting tough on migrants might play out well with the public, but anyone who has worked in an NHS hospital knows how crucial these workers are for the service.

As one A&E nurse at a central London hospital explains: “Within my department I’d say three-quarters of the nurses are from a different minority background; the NHS relies on migrant workers. Out of my colleagues there a lot of earning less than £35,000. These rules mean that it’s not about how well they treat patients, it’s about how much they earn.”

“These people have a life here, they’ve worked hard here for years and now we’re saying, ‘right, off you go’”.

Speaking at the RCN conference in June, one nurse said that already “huge swathes of the NHS are understaffed”. His was one voice among a chorus of concern.

Falling morale and rising stress have already taken their toll on hospitals’ abilities to retain nurses. With the pay-freeze now fixed for a further four years and, partly as a result, thousands of nurses set to be deported, there’s every danger that a precarious situation could be turned into a crisis.

“It’s really hard at the moment,” says the A&E nurse. “Morale is at the lowest level it’s ever been. We’re getting very close to a very dangerous point”.

RCN director of policy Howard Catton says that the Osborne’s pay freeze for public sector workers felt like a “bombshell” when he announced it in the budget.

He says: “We are very concerned about the impact on recruitment and retention, especially retention. Nurses are already faced with growing pressures and demand at work; in almost every workplace we’re seeing evidence of a shortage”.

But with the addition of the Home Office rules, he says, the situation could get alarming.

“It is perverse,” he says, “that we’ve got a set of immigration rules which could result in thousands of nurses having to go home if they don’t reach this threshold. The actual number of people in the UK affected as of April 2011 was 3,365, and that will go up to around 7,000 by 2020”.

The effect for the overall health service is worrying, but for individual hospitals and care homes, it could be devastating.

At one privately-run home which cares for a combination of individually-funded, local authority and NHS-supported residents, and whose staff is almost entirely made up of Asian workers, the manager – who did not want to be named – was furious.

He said: “This really is the most idiotic announcement I have heard, even from this government”.

What would happen to the home under these new rules?

“We would have to close,” he said, “or massively increase our fees and scale down our operation in the short term and our residents would have to find somewhere else to live. It would be heart-breaking for all our residents and their families, not to mention the staff.

“It would undoubtedly be terminal for some of our people, who have come to us for end of life care, and are very frail”.

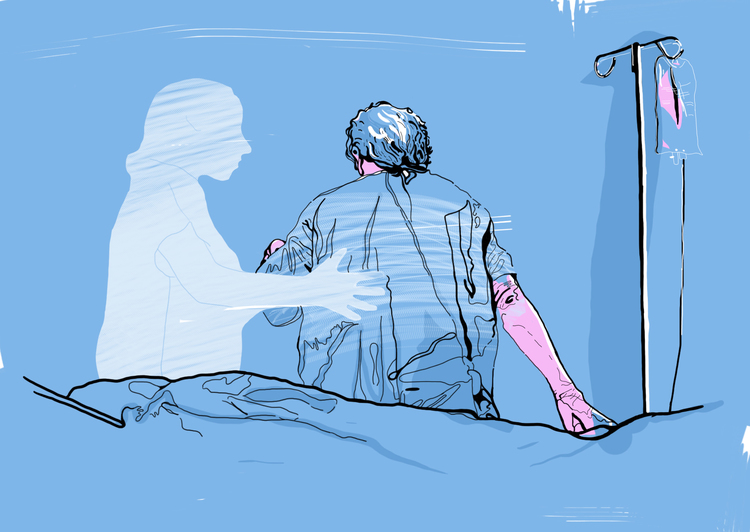

Illustration by Jennie Edwards.

Such drastic scenarios need to be avoided, for many reasons. As this concerned manager points out, the outcomes for patients in the home care sector alone could be severe; in acute hospital wards the consequences are too grim to contemplate.

But for the long-term health of the nursing profession too there are major repercussions.

Already recruitment is well below what it should be, and retention increasingly weak. Both of these problems are made worse by understaffing and the ongoing pay-freeze: reducing the workforce by deporting migrants will certainly exacerbate the former.

As Catton explains: “There’s a way to fix this which is to re-think the immigration rules. But the longer term issue comes back to the need to train more nurses and be better at retaining the nurses we already have in the system”.

Until a willingness to do either of these things is shown, the pressure is going to keep rising. The decision by NICE to go ahead and publish the A&E guidelines unilaterally is welcome. But the real question is how effectively NHS England will go about assessing and defining safe staffing now that it has decided to take it in-house – and away from an independent body.

At the moment there is little hope, it must be said, that nursing will be placed on the shortage occupations list and made exempt from the deportation rules. Citing the Migrant Advisory Committee, David Cameron himself said that this is off the table – despite the unassailable evidence from the RCN and others that it should be.

He said: “They [the MAC] haven’t put nursing on that shortage occupation list and I think we should listen to their advice above all.”

“With four more years of pay restraint, very little confidence that safe staffing level warnings will be heeded, and now, the threat of losing thousands of colleagues to reckless deportation rules, it’s a tough time to be nurse. ”

So there it is – once again the profession will have to make do. Unless the government listens to the unions and makes an exception on the basis of shortage, another blow to the safe staffing campaigners is on the way. And without the pay-rise so many had been wishing for, recruitment is going to suffer.

With four more years of pay restraint, very little confidence that safe staffing level warnings will be heeded, and now, the threat of losing thousands of colleagues to reckless deportation rules, it’s a tough time to be nurse.

It’s looking increasingly likely that the last resort of industrial action might go ahead sooner rather than later; indeed, at the RCN conference, that thorny debate was raised.

And is it any wonder, when nurses feel under attack from all angles by a government seemingly doing all it can, financially and politically, to drive them out of the profession they love?